REIMAGINING THE DINOSAUR

For the Australian music world it’s as if Apollo, god of music, woke abruptly in December with the Corona virus and sent classical musicians and opera practitioners off to their rooms to examine a world without music, as we witness opera companies close down on by one, orchestras send their players home on extended leave, and arts venues shut their doors. It is an extraordinary time in world history, and as we are pivoting away from the past and re-imagining our future, it is imperative that we strive for lasting change.

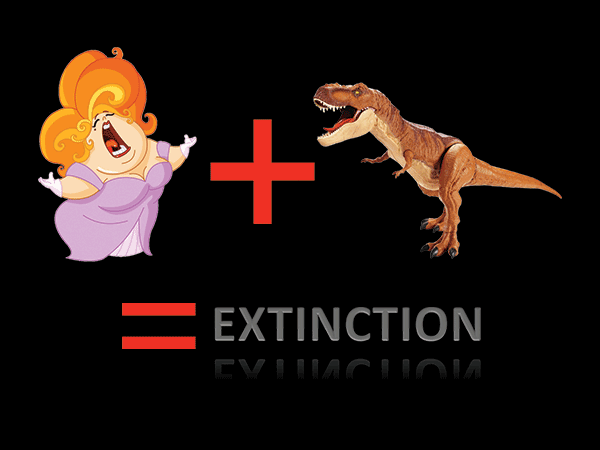

Opera is a 400-year old archaic, misogynistic dinosaur: a most magnificent beast with shiny, glamorous scales and a mesmerising roar, with a magical song line linking us and reminding us of its European cultural heritage. It is awe-inspiring; mystical; and riveting on first, second, and perhaps even third meeting for those who are introduced correctly to this expensive and otherworldly monster. However, we need to reimagine the dinosaur.

Currently, Opera Australia receives approximately $25 million per annum from the Federal Government. The various state companies also receive millions each year in funding. Every time an opera ticket is bought, the taxpayer pays $45 towards their experience at Opera Australia. For struggling Opera Queensland however, the federal and state governments combined have contributed $194 towards the cost of the ticket.

In 2014, a National Opera Review was commissioned to analyse the financial viability, artistic vibrancy, and audiences of Opera Australia and our state opera companies. With a worldwide decline in audience numbers for opera and the impact of the Global Financial Crisis, opera companies have been, and remain, in a state of crisis. In recent days there has been press about Opera Australia selling off its assets and staff being retrenched to stay afloat. If our major opera company falls, the future is grim for opera in this country.

An American neo-musical theatre rebirth has occurred within Australian opera companies, due to declining audience numbers and the expense of producing opera. These ‘Golden Age’ American musical-theatre works are propping up the companies, providing a safe programming option that guarantees box-office sales to mitigate the risk of programming traditional operatic works. Moreover, Opera Australia also now presents HANDA Opera on Sydney Harbour (HOSH). These productions are designed to attract tourism dollars, placing an iconic art form against an equally iconic backdrop in a city that suits large-scale outdoor performances. These two strategies, according to the National Opera Review, have contributed to increasing audience numbers for Opera Australia since 2015.

The National Opera Review also claims that the development of new works is too costly for companies. Yet Australian artists tell important stories that link today’s Australians to their heritage and help them connect more deeply to themselves. We have the oldest continuous living culture on earth, but we are still waiting for regular, new major operatic works to be commissioned by our opera companies which draw from the vast and profound wisdom of the Indigenous people of Australia and from Australian culture since settlement. Creating and incubating new, authentic works is a national imperative for the genre to survive. Yet there are committed, independent artists working tirelessly—like composer and soprano Deborah Cheetham—who are successfully composing using classical forms such as opera, oratorio, and song as vehicles for Indigenous stories and performers who have never been granted support by our opera companies. Another recent exception where a female composer has been given a major commission in the Australian opera world using Australian content was the Opera Australia commission of the opera Whitely by Elena Kats-Chernin.

For over 100 years, American and UK composers and lyricists have been incubating their own unique styles, where their Australian counterparts have very few opportunities to develop. The National Opera Review states:

[T]he renewal of the repertoire and Australia’s distinctive voice is not being heard and seen to the extent considered desirable. That trend is being amplified because new productions of existing works are increasingly being brought in from overseas or developed in partnership with an international company, which usually is the lead commissioning partner. While economically responsible, because it achieves economies of scale in the significant cost of physical productions, it deprives audiences of Australian-led creativity.

The development of new works is a vital part of Australia’s cultural identity in the world. It requires all levels of institutions, companies, and governments to adopt major incentives or infrastructures that enable the creation of new Australian-centric work, told from a balanced perspective of both genders. We are now at an unprecedented moment in history where the major companies will have to look to the small-to-medium sectors for new work to survive. Yes, it will be beyond difficult to stay afloat in the coming years for the small-to-medium sectors, but this is the silver lining at the end of the storm we are facing with the corona-virus crisis. Fundamentally, we require a radical shift in thinking and bold new leadership to effect such changes.

Music in Australia’s SWOT Analysis of Opera in 2017, states that, “the major State companies rarely independently build new productions. With the exception of productions jointly produced by the Opera Conference, most new productions produced for main stage presentation by the State companies originate at Opera Australia or overseas”. Unless a work is taken overseas, or is one of the few to be developed by Opera Australia, it is rare that it has the opportunity to be staged and toured in Australia.

Furthermore, for opera to have a future in Australia, we must be honest about what it has represented culturally for women. Moreover, our opera companies need to embrace inclusivity and diversity and look beyond what has already been done. New and younger audiences could be garnered if opera were reframed away from its sinister indoctrination and reinforcing of gender stereotypes. It is imperative that we encourage positive female narratives from composers and lyricists.

Several articles penned by Blackwood, Lim, Polias, and van Reyk in 2019 put forth a series of demands for opera in Australia to evolve in response to the male-dominated NOW opera workshops curated by Patrick Nolan from Opera Queensland and Scott Harrison from Griffith University. The article stated that opera must evolve “on our stages, in our creative teams, and on our panels”. Their call for a better, more inclusive vision for opera as an art form was both timely and necessary. Meanwhile the crisis worsens for opera talent at the coalface. After a public forum hosted in Brisbane by the Australian Women in Music Awards in October 2019 about the state of Opera in Australia, the Australia Council, the Australian Music Centre, and APRA AMCOS seem to have listened to the overwhelming tsunami of unrest within the industry and the demands set out by Blackwood, Lim, and van Reyk by responding with a round-table invitation-only discussion in December 2019 titled the Gender Equity and Diversity in Opera Summit. Time will tell if strategies can be implemented to effect systemic change when The Australia Council now faces the fallout of the corona virus or if it is up to the artists to risk livelihood and reputation by speaking up about such issues. After all, from the Suffragette movement to the protests that ended the Vietnam War, people joining together for what is right have won the biggest fights for justice last century.

If opera is to survive, our opera companies need to fearlessly examine the roles that women play in opera. Roles for women in opera are largely limited to roles of submission on stage. Many scholarly articles address women’s roles in opera on stage, including extensive work by Clément, Hutcheon and Hutcheon, Smart, Abel, and Klein. Dr Eve Klein asserts that “women [characters] typically die because they represent deviant behaviour embodied within a character flaw, occupation, ethnicity or social class”. Catherine Clément’s work challenges and reframes the representation of women of opera. She writes that the music of opera lures the audience into the operatic experience, causing them to forget the violence perpetrated against women. Examples include Butterfly committing hara-kiri as the climactic end to a marriage in which she bore a child to an American soldier; Puccini’s diva Tosca and the grim unfolding of suicide, murder, execution, and yet another suicide; the nuns in the final scene of Dialogue of the Carmelites who sing a beautiful chant to each other as they are sent, one by one, to their deaths by guillotine. It is time to challenge our creatives to turn the mirror and find a more balanced perspective for opera narratives.

A radical response is to commission new endings, re-structure narratives, create pastiches of well-known works and/or re-write some of the music for works in the operatic canon. Composers, directors, and lyricists could contemporise narratives to make many operas relevant today. Tosca could fake her own death and choose instead to live; Madam Butterfly could run off with Suzuki and her son and start a new life; Carmen could kill Don José instead, and the return of her music at the end of the opera could signify her triumph over a violent ex-lover. Such fresh and bold new treatments could create a new following for opera. Clearly, some may accept the plot presented by the lyricist and composer at the time of composition as integral to the works themselves and such conservative opera lovers will throw their hands up in dismay at this suggestion, but I would like to qualify that this idea has an important historical operatic precedent. Puccini’s Turandot was unfinished at the time of his death in 1924 and was completed in 1926 by another male composer, Franco Alfano. The first performance included only Puccini’s music, as Maestro Toscanini interrupted the performance where Puccini’s work terminated, but the second performance included the new ending, the version we know today. All this is to say that it is possible to rewrite, redirect, and re-interpret endings of operas and experiment with narratives with acceptance from classical-music audiences. I’m not advocating discarding traditional productions—I went into mourning the day Franco Zeffirelli died— but we should be simultaneously pushing the boundaries and fighting to reinvent it.

It’s not just on stage, but off stage too – and not just in opera: a lack of gender parity plagues many of our arts organisation boards. Of the 28 arts-organisation chairs in Australia, 20 are men, yet consumers of the arts in Australia are predominantly women. Dr Josephine Caust has done extensive research in this area and notes “[i]n a sector where women represent the majority audience as well as the majority of its participants, the low level of female artistic leadership is significantly out of tune with contemporary expectations.” Furthermore, whilst business expertise and matters of governance are clearly important, our boards are lacking members with direct experience of the machinations of an opera company. For any company to have few or no board members with arts experience, who then defer to Artistic Directors for every artistic decision, it creates a dangerous imbalance whereby artistic power and decisions lie with only one or a few.

In the 2018 Opera Australia season, only 23 of the 138 creative roles were filled by women, which equates to 16.6%, a decline from the 2017 figure of 18.2%. Yet other companies such as Belvoir, State Theatre of South Australia, and Queensland Theatre have all worked hard to achieve gender parity in writer/director roles in recent years. The 2018 Opera Australia season employed one female conductor out of 20 productions; one female director; and no female assistant directors, sound designers, or revival directors; but eleven female costume designers compared to five male! Their 2020 Sydney season over eight productions employs 85 creatives, 12 of them are female, a total of 14 per cent, again with a predominance of costume designers rather than other creative positions.

The other elephant in the room is Australian talent—trained here, often with massive taxpayer help— are overlooked for work, with opera companies employing second-rate offshore artists. It’s not just singers. Talent from every facet of the sector including directors, composers, instrumentalists, designers, and technicians are being consistently overlooked in favour of people from overseas. With the overseas travel ban implemented recently by the Australian government, that could stay in place for up to eighteen months, this will need to be re-addressed and quickly.

Australian-based artists and overseas-based Australian artists are often not even considered in the casting processes. Instead, they have been discarded like pieces of fast fashion hurled onto a sad, ever-growing pile of rotting Australian talent. These worthy artists have proven themselves on the operatic stage, and their consistent rejection hurts all artists who choose to remain in Australia.

The numbers are ugly and do not lie. The 2016 National Opera Review states that the number of performances by Australian singers in leading roles at Opera Australia plummeted from 778 to 383 between 2010 and 2016, a decline of 51 per cent. At the same time, the number of performances by international singers in leading roles at the company has grown more than four fold, from 60 to 251.

Our conservatories need to examine these numbers and consider if it is ethically responsible to continue to accept and train large numbers of vocal undergraduates. Australia has a long and distinguished history of producing world-class voices (to name just a few: Peter Dawson, Dame Joan Sutherland, Margreta Elkins, Donald Smith, Marilyn Richardson, Lisa Gasteen, Cheryl Barker, Emma Matthews, Catherine Carby, Nicole Carr. The list goes on), but with declining career trajectories and opportunities to hone their craft available for our young operatic graduates in Australia, the economic realities of a career as an opera singer are becoming ever more challenging. The selection of talent for undergraduate and postgraduate courses needs to become more competitive and numbers should be limited. Postgraduate students should be encouraged to train overseas in countries that can embrace and provide opportunities for our young artists in their future careers unless our institutions can lobby our opera companies and the Australia Council to rectify this imbalance. Furthermore, with the revival and trend for musical theatre to prop up the box offices of our opera companies, there is a real need for our singers to diversify their training. We must be training our singers to cross over into singing in other genres, such as musical theatre, jazz, and contemporary singing, to prepare them for the real world of freelance singing. The current generation of young opera singers I work with, who are studying operatic technique, also listen widely to musical theatre, pop, jazz, and world music. There is an almost tangible joy in discovering the joys of music beyond their classical training where they learn to play and experiment with the voice. This overall tendency for singers to look beyond their own backyard is a welcome change to breaking down the boundaries across genres to allow for growth and rejuvenation. Graduating singers must learn how to navigate different styles and how to do so healthily beyond the confines of their own shower cubicles, with proper instruction. Not educating our singers on how to sing functionally in alternative styles, in addition to their predominant classical style, is a detriment to their career. A suitably trained singer for the 21st-century singer needs to sing across multiple genres, act, analyse text, dance, speak, and translate multiple languages, be strong and fit enough to take on roles with significant physical demands, and interact effectively with colleagues.

In the London-based classical-music publication Bachtrack, internationally renowned Australian tenor Stuart Skelton recently criticised Opera Australia for flying in “every second-rate singer from anywhere to sing stuff when we’ve got people in Australia who sing those roles just as well”.

Principal Australian tenor, Rosario La Spina and his wife, mezzo-soprano, Milijana Nikolic, became so frustrated with the lack of opportunity, they abandoned their home base of Brisbane and moved back to Italy mid career. They are now stuck in Italy amidst the corona virus wishing they were in Brisbane with their family and friends.

“If an Australian-based singer has experience and is well suited to the role, then they should be the first ones cast” La Spina said.

“Preference should go to overseas Australian singers – if they are doing well overseas then it should be a no-brainer that they are invited back to sing for Opera Australia.”

Nikolic added: “It is disappointing that because of lack of opportunities singers with experience and talent need to leave for overseas to earn a living. Or in many cases they have to change their profession altogether and stop singing.”

If roles cannot be filled locally or with relative ease, then why is certain repertoire being suggested? Now is the time for changing these colonialist attitudes. If and when money is again invested back into the Arts by the federal government, employing musicians we have trained in taxpayer-funded Australian institutions for works that suit their talents is an effective, responsible utilisation of public money and a perfect example of a circular economy, minimising waste and making the most of our rich artistic resources.

In contrast to many other international opera destinations, Australia is massively disadvantaged by the tyranny of distance. However, this very disadvantage offers an excellent opportunity to program operas that feature Australian-based opera singers, to develop home grown audiences who know the names of our artists, (bring back the local star system and let’s ditch the generic photo with a model with the title of the work on it – but that is another article), and to develop a healthy work culture for our artists, only importing singers and conductors for specialist works. This approach would create an economic counterforce that would help in the creation of works of art unique to this region, while protecting local income. But it will require a serious shift, not only in the thinking of opera companies’ leaders and conservatories, but also in their very leadership styles.

The reality of being a mid-career operatic artist in Australia is tough and not for the faint at heart. Many are now facing unemployment and the cold breath of financial ruin. Opera singers are too scared to speak out about anything for fear of never being employed again, not only at Opera Australia, but also at the state companies where singers cling to any morsel of operatic work thrown in their direction. Artistic directors must think beyond their own personal legacies and do everything in their power to support the locally based Australian opera singers and classical musicians as the crisis worsens at the coalface in the Arts sector.

Opera is an art form that demands excellence, personal sacrifice, and years of expensive training. It is an insult to those working in the art form to fill a role with an actor or director from the theatre world. We need opera experts who have spent their lives studying this intricate art form. The same expectations must be placed on the governance and management of opera companies management. Fundamental knowledge of the art form they are representing must be a priority, particularly when casting and rehearsal processes are being determined. Given the vast sums of public money pouring annually into the coffers of Opera Australia and the state companies, audiences and practitioners have every right to demand the engagement of Australian artists and expert industry personnel as a managerial priority. It is time for an independent body to oversee opera boards and their long-term strategies, because ultimately these boards make the fundamental decisions for the art form.

Genres such as theatre, literature, and film have reinvented themselves using early works as benchmarks for style and structure to inspire and innovate new visions of those genres that can attract younger audiences without a crisis. Now we are living through one, so can opera. Without one, opera will be seen as null and void by the masses. Those presenting opera should be seeking new answers and possibilities beyond what has already been done. We should make it a national priority to provide work for Australian-based opera singers who choose to live here. Creating and incubating new authentic Australian works, employing and nurturing Australian-based artists as the first priority—and the distinctive voice and home-grown star structure that will emerge from such initiatives—is a national imperative for the survival of the genre and our artists. New and younger audiences could be garnered if it was reframed away from its sinister indoctrination and reinforcing of gender stereotypes. It is imperative that we encourage positive female narratives from composers and lyricists, led by management and creative teams with an equal balance of gender.

The opera world desperately needs a rebirth from the top down and a meta-modern revival that examines a new way of dealing with the past in alignment with current dominant sensibilities in the digital age. If we don’t redress the dinosaur for the modern age, it will surely face extinction.

Works Cited

Clement, Catherine. Opera, or, The Undoing of Women. University of Minnesota Press, 1988.

Commonwealth of Australia. National Opera Review, 2016. www.arts.gov.au/sites/g/files/net1761/f/national_opera_review_final_report.pdf. Accessed April 20 2019.

Klein, Eve Elizabeth. The Pomegranate Cycle: Reconfiguring Opera through Performance, Technology & Composition. Queensland University of Technology, 2011.

Meconi, Honey. Early Musical Borrowing. Routledge, 2004.

Music in Australia (n.d.). SWOT Analysis of Musical Theatre – the Australian Musical.musicinaustralia.org.au/index.php?title=SWOT_Analysis_of_Musical_Theatre_-_the_Australian_Musical. Accessed April 21 2019.

Neill, Rosemary. “Opera Australia boss Lyndon Terracini: democratise or die”. The Australian, 15 March, 2014.

Senczuk, John. The Time is Ripe for the Great Australian Musical (Platform papers). Arts Music Theatre Australian Public Policy. Currency House, 2015.

Tilden, Imogen “Opera can make us see, feel and hear the world differently: the UK’s opera chiefs tell us why their art form matters”. The Guardian, 9 May, 2014. www.theguardian.com/music/2014/may/09/inside-opera-live-why-opera-matters-uk-opera-chiefs, 2014. Accessed March 13 2019.

Westwood, Mathew. Author Pushes Creative Approach to reinvigorating cultural leadership. The Australian, (Review of Dr Josephine Caust’s book – Arts Leadership in Contemproary Contexts) August 16, 2018

Žižek, Slavoj and Dolar, Mladen. Opera’s Second Death. Routledge, 2002.

Works Consulted

Beer, Anna. Sounds and Sweet Airs – The Forgotten Women of Classical Music. One World Publications, 2017.

Bu Caust, Josephine (2018) Arts Leadership in Contemporary Contexts, Routledge Advances in Art and Visual Studies, Abingdon: Routledge. IBSN 978-1-138-67731-9

Butler, Judith. Gender trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity, 3rd ed. Routledge, 2006.

Edwards, H. Sutherland. History of the Opera from its Origin in Italy to the Present Time With Anecdotes of the Most Celebrated Composers and Vocalists of Europe. London: W. H. Allen & Co., 1862.

Friedan, Betty. The Feminine Mystique. Norton Paperback, 1963.

Tarita Botsman is a Brisbane based writer, director, actress and opera singer who is currently completing her PhD in Music at the University of Queensland. She is the Chair of the Classical Music Committee of the Australian Women in Music Awards, founder and artistic director of The 7 Sopranos and a former Young Queensland and Young Australian of the Year for her contribution to the arts in Australia.